I teach an upper-level undergraduate college literature course titled Shakespeare in the World. Having just come back from sabbatical, I decided to teach plays that I enjoyed, giving the course the subtitle “A Few of Fowler’s Favorites.” A nice, easy glide back into the teaching routine, I thought. Then, on Sept. 10, Charlie Kirk was shot. A week and a half later, I was slated to start Macbeth.

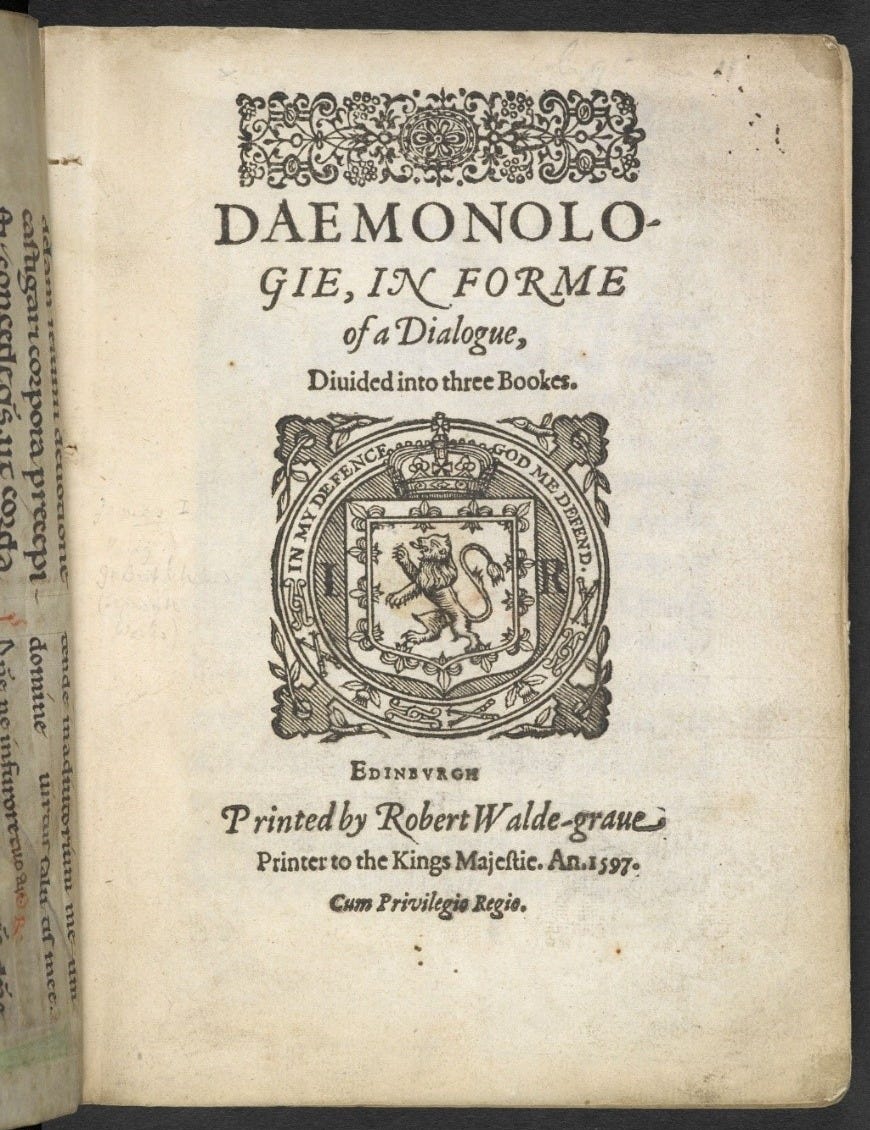

I began the unit with a video by Dr. Ryan M. Reeves on King James VI of Scotland and I of England’s obsession with rooting out witches, including his writing of the tome Daemonologie in which he explains how to identify, capture, and torture witches. Literal witch-hunt stuff. For those of you wondering, yes, this is the King James of the bible translation. And yes, he actually had “witches” tortured and executed. In fact, Scotland at the time of his reign was a hotbed of witch-hunting fervor.

My rationale was this: context is important. Shakespeare wrote “The Scottish Play” for King James, a major patron of his acting troop. A Scottish play seemed smart, and including witches pretty on-the-nose. Introducing the play this way opened the door for discussing with the class the play’s non-ambiguous focus on gender, and in particular, masculinity.

Yes, that’s right; even Shakespeare may be read as having “woke” representations of gender identities, as his characters frequently desire to—and do—step outside the norms. For instance, most of the women in Macbeth defy femininity. The witches are notably described by Banquo as “bearded,” confusing his easy identification of them as women while also acknowledging their uncanniness. Lady Macbeth calls on “dark spirits” to “unsex me here” so that she can complete the violent acts afforded to men but not to women.

When her husband, the eponymous protagonist of the play, balks at her plan to murder King Duncan and seize the Scottish crown (the witches had prophesied that he would be king, after all!), she emasculates him with her language, telling him, “When you durst do it [murder Duncan], then you were a man; And to be more than what you were, you would be so much more the man.” Macbeth, for his part, says that he “dare do all that may become a man.” That is to say, he will commit murder. But, when he returns from having completed the deed, in shock and still holding the bloody knives, it falls to Lady Macbeth to return to the murder scene and plant the evidence on the drunk and sleeping guards. She takes on the mantle of the “rational,” unemotional man and finishes the setup.

Violence, in this play, is manly.

And yet . . . and yet. So too is the capacity to grieve. When Ross shares with Macduff the horrible news that his wife and son have been murdered at Macbeth’s orders, the slain Duncan’s son Malcolm tells Macduff to “dispute it like a man.” Macduff responds, “I shall do so, but I must also feel it as a man.” These men, having flown to England to begin plotting the tyrannical Macbeth’s overthrow, speak of revenge.

Yet.

Yet.

Macduff takes the time to mourn his losses.

In the play, a bloody tyrant’s reign can only be met with more blood. This is a warrior culture. Bloody hand-to-hand combat is what they know. Still, Macbeth hesitates to commit regicide. Macduff pauses before avenging the deaths of his wife and son and the “downfall’n birthdom” of their homeland. “Bleed, bleed, poor country!” he laments. The only way forward for Macduff, as with Macbeth, is to claim control of the country through political violence: war; murder; revenge.

Yet.

This brings me, and the class, to the current moment. To The Manosphere. What does it mean, today, to be “so much more the man”? Does it require violent action?

Tyler Robinson’s motive for shooting Charlie Kirk to death remains unclear; indeed, it appears to be quite complicated. His own texts claim that he had “had enough of [Kirk’s] hatred,” and it seems that some of the hatred he’d had enough of was Kirk’s disdain for the trans community, since it also seems likely that his roommate and significant other was transitioning from biological male to female. Most accounts also note that Robinson didn’t appear to be outwardly political himself, though his family voted Republican, and they they appreciated and sported with firearms. More reports address the 22-year-old’s engagement with video games and Discord channels and suggest his potential radicalization there, though radicalization to what is uncertain.

Nonetheless, the shooting raised the specter of political violence, with some on the right calling for retribution, among them Vice President JD Vance and Fox News’ Jesse Watters. While some on the left purportedly celebrated the untimely and horrible death of a 30-year-old man with whom they had political differences, the most visible publicly decried this senseless act. Meanwhile, the President of the United States expressed hatred of his opponents (which his press secretary Karoline Leavitt claimed makes him “authentically himself”). This in direct defiance of the message of forgiveness shared by Kirk’s widow, Erika. Both comments were made at a huge public memorial service for Kirk.

Conversely, political violence committed against those on the left, such as former Minnesota state Representative Melissa Hortman and her husband, were largely ignored by the right (“I’m not familiar. The who?” Trump said when asked it would not have also been appropriate to fly the flag at half staff after her murder, as it had been for Kirk). Or, worse, it was mocked, as with Paul Pelosi’s brutal attack in his home with a hammer in 2022. The POTUS and his son both sneeringly poked fun of the 82-year-old man who suffered a skull fracture as a result of the attack.

As Kirk was set up as a martyr for the MAGA cause, for Christianity, for traditional values, fears of further political violence increased, and for good reason. It was highly likely to happen . . . and DID happen. On Sunday, Sept. 28, Thomas Jacob Sanford drove his truck through a wall of a Mormon church in Grand Blanc, Michigan, opened fire, then set the building aflame, killing four people and wounding still more before being shot by police. Sanford had, in the past, referred to Mormons as “the antichrist.” Charlie Kirk’s shooter was a Mormon. Was there a connection?

If there is one thing that both Macbeth and the shooting of Charlie Kirk and its aftermath have shown us, it’s that violence begets violence. What all of the rhetoric surrounding this tragedy also shows us is how easy it is dehumanize others. When we remove basic humanity from people outside our in-group, it’s exponentially easier to inflict pain and suffering—and even death—on them. Acts like those carried out by Robinson and Sanford feel justified. Robinson no longer saw Kirk as a man, but rather, as Hate personified. Sanford saw the worshipers at the church in Grand Blanc as the antichrist because of past experiences with a Morman girlfriend in Utah. For him, all Mormons were evil. This is genocidal thinking.

“Witch,” “hate,” “antichrist.”

Words and names can, in fact, be a precursor to harm, even if our First Amendment grants us the right to use them. Hence, all of the talk about “violent rhetoric” and who needs to control it. Ask the the Left, and the Right needs to work harder to bring the temperature down. Ask the Right, and the Left is is blame for turning it up.

Still to this day there is hullaballoo over Hillary Clinton’s reference to some conservatives as “a basket of deplorables.” Frankly, I agree with this criticism. This is dehumanizing language, and many on the right (and some on the left) called her out for it. Surely, then, the Right would work extra hard to check their own language, yes?

No. Instead, Donald Trump has upped the ante on dehumanizing others. For example:

Democrats are called “the enemy from within.”

Both political opponents and immigrants are referred to as “vermin.”

Democrats, immigrants, and sanctuary cities are labeled “garbage.”

Immigrants are declared “the worst of the worst.” His claims to only be rooting out the so-called “worst” is undermined by the thousands of hard-working migrants that have been rounded up by ICE.

Immigrants are said to be “poisoning the blood of our country.” I’m not kidding. People don’t like comparisons, but Trump isn’t the first to talk about national “blood purity.”

Immigrants are “animals.”

One-time political allies who have spoken out against him are “traitors.” He’s said they should be arrested for treason.

Democrats and liberals are “the radical left,” regardless of how center-left they may be.

Anyone who opposes his policies and executive orders is “un-American” and a “terrorist.” Today, I learned that “House Speaker Mike Johnson and House Majority Leader Steve Scalise referred to the peaceful ‘No Kings’ protest planned for October 18 as a ‘Hate America rally,’ House Majority Whip Tom Emmer went one step further, calling it a ‘terrorist’ event.”

Protestors who stand up against his policies and rhetoric are a “left-wing mob” and members of Antifa.

Any news outlet that doesn’t represent him favorably is “fake news media.”

Democratic-led cities are “hell holes” that need to be brought to heel.

Trump calls for Democratic leaders who fight his deployment of the National Guard, other military branches, and ICE into their cities to be arrested, and ICE detains a journalist in Chicago.

Again, he flat out said he “hates” his political opponents. He wants his supporters to hate them, too. It makes it easier to justify political violence against them.

(This is not an exhaustive list.)

Full disclosure: I oppose Trump’s presidency. Not because he is a Republican and I tend to vote Democratic (in fact, I am pro-democracy and vote my conscience, which means I don’t always vote blue), but because he espouses dehumanization in both words and action against anyone who disagrees with him. I think he’s tyrannical.

For those who may be wondering, no, Trump did not come up in my class session on Macbeth. But, the dangers of dehumanization and tyranny did.

I am a Compassion Ambassador. Compassion necessitates awareness of our shared humanity. To start this class period’s conversation about political violence, my students practiced an activity called “Just Like Me.” In this practice, individuals sit face-to-face with a partner and silently repeats phrases that are read aloud to their partners. Phrases include some of the following:

This person has at some point been sad, just like me.

This person has been disappointed in life, just like me.

This person has sometimes been angry, just like me.

This person has been hurt by others, just like me.

This person has felt unworthy or inadequate at times, just like me.

This person worries, just like me.

Please see the “Just Like Me” link for more.

It’s a powerful practice that invites participants to recognize the humanity of the person seated across from them. It sets the tone for difficult conversations that leave room for hearing differing perspectives and disagreeing respectfully because we now recognize that others in the room have human experiences “just like me.”

Our discussion of masculinity in the play and the manosphere in contemporary life and definitions of types of political violence (e.g., war, terrorism, pogroms, genocide, disappearings, assassination, rebellion, rioting) followed before we had a discussion about two short readings I had assigned as homework: “Fierce Extremism Calls for Fierce Compassion” by Victor Calderola and an open letter, sent to both JD Vance and Donald Trump titled “A Call for Compassionate Leadership”). We unpacked the terms “tender compassion,” “fierce compassion,” and “warrior compassion,” the latter two described in Calderola’s piece. This led to some excellent discussion and consideration.

Some students felt very strongly that they could have compassion for those impacted by Kirk’s shooting, including his wife and children and those who were present at that moment, but not for Kirk himself. For them, much as for Robinson (but thankfully in a nonviolent manner), they viewed Kirk as a spreader of hate. I acknowledged their perspective, validated it, then explained why I think it’s possible to hold compassion for someone with whom we vehemently disagree. I did not say, “You are wrong”; we had a conversation.

Another student referenced something he’d recently read by Archbishop Desmond Tutu on forgiveness and suggested that, perhaps, compassion was only possible if forgiveness came first. After all, this student noted, Tutu, a South African, had faced persecution during Apartheid. If he can forgive, can’t we all? I disagreed with one aspect of my student’s claim: I believe compassion is possible without forgiveness. I did not tell him he was wrong; I shared my point of view and asked him what he thought.

We talked about the challenges of holding space and allowing compassion for those with whom we disagree or find challenging. I reminded my students that compassion only exists in the presence of suffering. That it requires us to identify suffering, affectively respond to that suffering, wish to do something to alleviate it, and then act on that wish in any manner available to us. We talked about knowing what we are able to offer to the sufferer (wisdom) and to face that suffering and act (courage).

We talked about the controversy over the phrase “thoughts and prayers” and came to the consensus that this is a perfectly legitimate response in the face of suffering if 1) the offerer believes in the power of well-wishing and prayer (good-faith offering) and 2) it is, in the offerer’s wise discernment, what is within their means to offer. We also addressed the possibility of the meaningfulness of this offering to those for whom prayer is a powerful salve.

However, when the sense is that those offering “thoughts and prayers” have the capacity to offer more, this is seen as a bad-faith offering, mere lip service to compassion when greater action is possible. Of course, this was especially viewed by the students as the problem with legislators tepidly making this statement after yet another school or event is peppered with gunfire, resulting in the loss of numerous lives. Or when a popular podcaster is shot dead. “They can do more” was the common sentiment in the class.

I shared that, while it is hard to hold space for those whom I find difficult or with whom I have serious disagreement, I can still find room for compassion. I recognize, first, that the compassion I need to offer may be for myself. It’s possible the other person isn’t actually suffering and in need of my compassion. It’s also true that compassion can mean saying “no” or “enough” and standing up for our rights.

Secondly, as tired as this adage may be, I recognize that “hurt people hurt people.” If what an individual says and does is legitimately hurtful and harmful to others—if it dehumanizes them—then there is suffering present. What has brought this person to the point that they feel the need to demean, belittle, or dehumanize others, whether individually or as a group? What suffering is there? For that I have compassion. They are, after all, a fellow human being.

For many in the manosphere, that suffering is related to fear of “replacement.” It is rooted in “the need to defend its sociopolitical hegemony,” according to Alexander Faehrmann and Dr Steven Zech in their 2023 essay “The Great Replacement in the Manosphere: Implications for Terrorism.” I see that fear as suffering. I feel sympathy for that fear because I recognize that I have also been afraid and among my fears has been the fear of abandonment. What is the fear of “replacement” but a fear of being abandoned? With this I can empathize. I wish to alleviate that fear of abandonment, so I consider what tools I have at my disposal to work toward that end. And then I act.

My tools to address this suffering? Macbeth. Research I’ve done on masculinity (primarily on how men grieve). Articles on compassion in the face of political violence and extremism. The Applied Compassion Training program I went through. My classrooms.

Some might accuse me of indoctrinating my students because of this. Perhaps they’d even record me and turn me in to Turning Point USA’s Professor Watchlist as a radical. If I am a radical indoctrinating them into living a more compassionate life, I say, “Accuse away.” I hold on to the fact that three students, two of them men, approached me after class—one actually started to walk through the door and then came back in—to tell me how much they appreciated this conversation and to encourage me to address big issues more often. They made clear that, for them, this is what college should be. I agree.

We didn’t debate. I didn’t say to my students, “prove me wrong.” We had a respectful conversation.

Is it easy to hold space for those men who think we should return to a time when women should be only wives and mothers (I am neither)? Who say women should be content with staying in the the domestic sphere rather than having careers (again, not me)? Who believe women should be deprived of the right to vote (I am proud to be able to do so)? Who, in the time of King James, might think women like me a witch? No. Compassion is not easy.

Do I have compassion for President Donald J. Trump, even if I disapprove of his presidency? I do.

I believe he suffers from a need to be accepted and that his hunger for acceptance is boundless. He has worried about being accepted and having others like him, just like me. As a social anxiety sufferer, I understand this is a moment of suffering. I would like to be able to take away his need to be lauded, his outsized desire to be seen. I think this would make a big difference in how he sees other people. So, what is within my power as an offering to alleviate his suffering?

Thoughts and prayers.